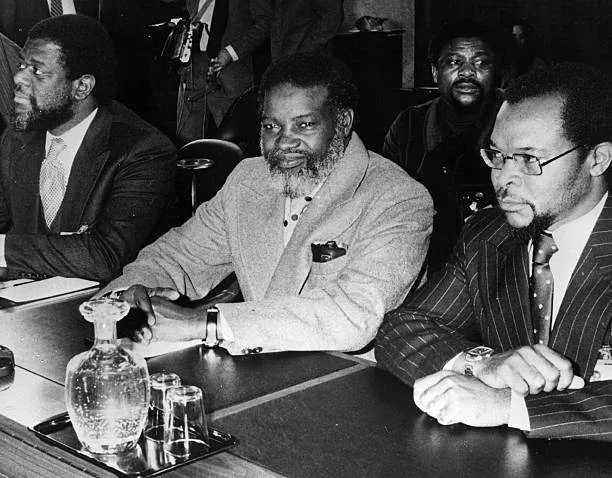

The delegation of South West Africa Peoples Organisation (SWAPO) with its President Sam Daniel Nujoma, centre, Hidipo Hamutenaya,...

KONGWA

In contrast, the long-reading article highlights the experiences of Namibians who were living at Kongwa during the 1960s. Drawing on the recorded history, interviews and published personal memoirs such ANC’s Morogoro Papers, and Tanzanian testimony, it argues that Kongwa has shaped a social hierarchy among exiled Namibians and non-Namibians who lived around the camp. The article sheds lights on the true history of how Kongwa camp was formed; how SWAPO related to Tanzanian government and other liberation movements and how such relationships construeted a radical resolution to handle or curb conflicts within SWAPO. I emphasise that our history is very obscured!

Thus, in Namibian historiography, Kongwa testimony reflecting not only SWAPO's rejuvenation but also represents the imperfections of the liberation movement (‘Kongwa Crisis’) for instance, the comrades who were based at Kongwa in 1968 openly criticized the SWAPO leadership and many were indemnified, detained or tortured by their own fellow comrades. While Kongwa has an important contribution to our Namibian historical knowledge, it also equals important to review the other version of Kongwa as part of a nation’s history where ‘heroes’ and ‘villains’ in narrow nationalist narratives have created. I personally have no bad hiccups with the mighty SWAPO party, where we have born and raised, but the truth should be told!

In contrast, this article describes the daily life of SWAPO at Kongwa and relates the tensions which developed among Namibians who were there during the 1960s. I am arguing that some SWAPO officials are responsible for the witch-hunts at Kongwa and misused of their level privileges at the camp to manage conflicts emerging within it. This perspective is obscured in histories of ‘the Kongwa Crisis’, which focus on the role of a few individuals in a national liberation struggle rather than on the international relations which enabled elites to speak on a nation’s behalf include those who not a bind to the same ideologies.

Kongwa's narratives based on true oral testimonies of Namibian liberation icons who witnessed and experienced the events at Kongwa plus the archives of other independent parties, which extend these testimonies beyond the national frames. By drawing attention to Kongwa as a lived space, this article provides insight into social contexts from the 1960s that blended the consequences for post-colonial Namibia. It illuminates young people and refreshes the minds of comrades who experienced the past and still facing the same grievances in the present.

OAU FORMATION

On 25 May 1963, the Organization of African Unity was formed in Addis Ababa. Among the agencies established under the auspices of the OAU was the Co-ordinating Committee for the Liberation of Africa, which soon became known as the ‘OAU Liberation Committee’. Tasked to harmonize, provide assistance in aid for the African liberation struggle; manage the fund, encourage, coordinate their efforts and establish united fronts wherever necessary and reconcile the conflicting among liberation movements. Importantly, the Liberation Committee’s headquarters were set up in Dar es Salaam, Tanzanian (then Tanganyikan) government, led by Julius Nyerere.

KONGWA ESTABLISHMENT

By the mid-1960s the number of southern African exiled cadres in Tanzania was growing exponentially. It led political activists and each liberation movement to establish the office in Dar es Salaam for their liberation wings include those were seeking recognition from the Tanzanian government. In the case of SWAPO, the majority of exiled cadres who entered Tanzania during the early 1960s were contract workers recruited in Francistown, Bechuanaland (now then Botswana). In 1962 and 1963 SWAPO transferred some of these exiled members from Tanzania to Egypt, Algeria, the USSR and China where they participated in military training courses alongside exiles from other liberation movements.

Other exiled members enrolled in schools, above all Kurasini International Educational Centre, a secondary school catering scholarships which were established by the African-American Institute in Dar es Salaam to prepare southern Africans for tertiary studies. When other people found themselves without any occupation or place to stay and they moved into overcrowded refugee camps administered by humanitarian organisations on the outskirts of the city. It is in this context that the Tanzanian government, on behalf of the liberation committee, set aside a tract of land ''KONGWA camps'' in central Tanzania for the African liberation movements. The land was situated at the site of an abandoned school and railway station located less than two kilometres west of main Kongwa village and eighty kilometres east of Dodoma.

According to Samora Machel, he and other FRELIMO cadres who arrived at Kongwa and began to construct the camp on 4 April 1964. Similarly, John Otto Nankudhu, one of the first group of SWAPO guerrillas to inhabit Kongwa, indicates that he and his fellow Namibian comrades arrived at the site around April 1964 and, within two days, were joined by a larger group of Mozambicans led by Samora Machel. Over the next several weeks, SWAPO and FRELIMO members renovated the dilapidated school building into soldiers’ barracks, constructed new buildings to be used as offices and kitchens, and separated the two movements’ camps with the barbed wire fence.

In all these activities, the liberation movements were aided by local Tanzanians who, at the request of Tanzanian government officials, helped the camps’ construction and provided food and drink for the workers. By May the Namibians and Mozambicans had moved out of their tents, which they had pitched in the bush near Kongwa, and into their respective camps. Driving the rough, gravel road between Dar es Salaam and Kongwa was a full day’s journey, and although there was a railway stop located fifteen kilometres northeast of the camp along the line running inland from Dar es Salaam to Lake Tanganyika, the liberation movements’ access to the railway was restricted by the Tanzanian government.

The territory surrounding Kongwa was sparsely populated. The village around Kongwa was inhabited by no more than 1000 people. It lays as farmland with small, shifting settlements occupied by people who collectively referred to themselves as ‘Wagogo’ depending on agriculture, cattle raising and nomadic immigration. Before that, in late 1940s Kongwa briefly became a site under a massive development project of British known as the ‘East African Groundnut Scheme’and, by the 1960s, some Wagogo had entered Tanzania’s migrant labour system and were selling groundnuts (karanga) in a cash economy.

In the beginning, FRELIMO combatants were the majority presence in this community. According to Samora Machel, by September 1964 Kongwa had already accommodated at least 250 FRELIMO guerrillas who, following military training in the camp, infiltrated Mozambique and initiated the armed struggle. In 1966 majority FRELIMO vacated Kongwa and hundreds of FRELIMO guerrillas moved to the camp and locations in Mozambique where they were involved in military operations and supplying those living in the liberated zones. In contrast, the group of SWAPO guerrillas that established a foothold at Kongwa in April 1964 consisted only numerous individuals. Nevertheless, their numbers did increase rapidly when dozen of FRELIMO trying to set their presence closer to Mozambique.

According to one source, by the latter part of 1964 there were roughly over 100 Namibians living at Kongwa and, by the middle of 1965, there were nearly 300. For the most part, these guerrillas remained inside the camp with only small groups departing from it to infiltrate Namibia in the latter part of 1965 and 1966 onward. Within a year or so of the first camps' openings, other liberation movements also followed. In August 1964 the ANC founded its camp within the vicinity of the area. Located on the site of the old railway station about 50 metres outside the SWAPO and FRELIMO camps, the ANC camp was first inhabited by Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the cadres returning from military training in Egypt and the USSR respectively.

The numbers increased very quickly such that by the end of 1964, there may have been 400 to 500 South Africans living in the camp, making it the second largest at Kongwa. At least four of these first MK cadres at Kongwa were women, contrasting with the SWAPO and FRELIMO camps where there appear to have been even fewer women at this time. In 1965 the MPLA and ZAPU also set their presence at Kongwa, initially, these two were located some three kilometres from the SWAPO,FRELIMO and ANC camps. Numbers fluctuated considerably in the MPLA camps. Thereafter the leaders of the liberation movement capitulated the advantage of the newly Zambian independence in 1964. Zambian government already recognised them as early as 1965 by opening a new front along the Zambian-Angolan border. Nevertheless, during the mid-1960s both the MPLA and ZAPU camps still remained relative to the camps of FRELIMO, the ANC and SWAPO.

In addition to the liberation movements which were officially inhabiting Kongwa, there were also other groups which were not recognised by the OAU that were hibernating within the recognised liberation movements’ camps. For example, in 1965 and 1966 at least eleven soldiers aligned with Jonas Savimbi and UNITA were staying together with SWAPO’s camp. Savimbi had recruited these soldiers from the Angolan community and let them live in the Zambian Copper belt, and then he drew special recognition at the OAU through his close personal relationships with several SWAPO and Tanzanian officials to smuggle them into China for training and then back to Zambia while awaiting passage en route to their various assignments in Angola.

At the same time, there were others within the SWAPO camp who, prior to entering exile, had belonged to the Caprivi African National Union (CANU), a liberation movement which claimed to represent Caprivi region. Although CANU officially merged with SWAPO in November 1964, some Caprivians continued to identify themselves as CANU patriots and unwavering only recognise CANU leadership structures even as they resided within the camp granted to SWAPO. Thus, CANU too could be counted among the liberation movements based at Kongwa despite the fact that the movement and the territory which it claimed to represent were not widely accepted.

READ NEXT PAGE [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

.jpg)

.jpg)